- The policy was part of BJP's manifesto for the 2014 general election

- The NEP will likely not see the light of day during the present government

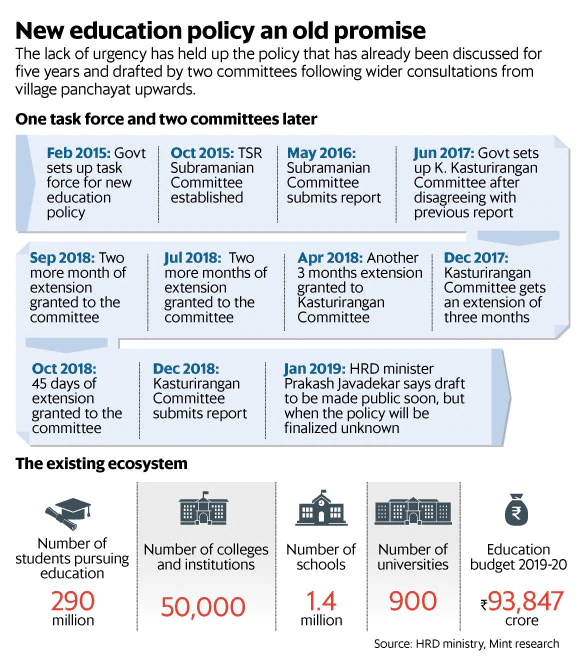

Five years, two committees and 115,000 consultations later, India's proposed new education policy (NEP) is still a work in progress.

Back in the 2014 general elections, the Bharatiya Janata Party's manifesto promised a new education policy that would "meet the changing dynamics of the population's requirement...".

The NEP assumes significance as it comes after a gap of nearly 30 years and will be a key document for a burgeoning sector that has a direct impact on 290 million students or almost 25% of India's population.

Once in place, the new policy will have to deal with a country that has changed significantly post-liberalisation, lack of jobs and the industry 4.0 phenomenon that makes routine work redundant, putting humans in competition with machines.

Throw in the dismal quality of education, and what emerges is a burning need for a new education policy with a clear direction on quality, innovation, outcome and industry linkage.

However, procrastination has held up a policy that has already been discussed for five years and drafted by two committees following wide consultation from village panchayat upwards. With only months to go for general elections, there is hardly any time left for the policy to get parliamentary approval.

The NEP will likely not see the light of day during the present government.

"A broader education policy is a need for systemic reform of the sector - in academics, in regulations and in financing," said Parth J. Shah, an education economist and head of the Centre for Civil Society, a think tank. "The delay is a sad commentary on the importance that education gets."

Experts and academics said the exercise that has been undertaken is huge and the consultation process robust.

"The promise of NEP has been belied as the goal posts for announcement of the policy have been shifted from time to time...Huge resources invested in nation-wide consultations by the high-powered committees headed by T.R.S. Subramanium and K. Kasturirangan have been wasted," said M.M. Ansari, a former member of the University Grants Commission.

Human resource development minister Prakash Javadekar said in January that the second draft is ready and will be made public soon for feedback for the final policy. An HRD ministry official, however, said that this was "unlikely" now.

"The exercise has been good and we shall make sure that the policy has a vision for the next 20 years. We know, it's late but rushing it at the fag end of a government's tenure may not be the best solution," the official said, requesting anonymity.

India's first education policy was framed in 1968 based on the famed Kothari Commission report, the second in 1986 and the third—a revision of the 1986 policy—in 1992.

The official cited above said it's not as if the previous policies were implemented quickly. In fact, making eight years of education compulsory was part of the 1968 policy but it was implemented only in 2009 through the Right to Education Act.

Shah said the policy must make provisions for segregation of the governance structure. Instead of one department doing everything, there has to be one agency looking after policy and finance, another on regulations and a third on adjudication. "There has to be strict regulation based on performance and there is need for rules to make parents important in government schools to improve outcomes."

Ansari said school education needs a huge improvement if India is to reap the benefit of its young demography, helping feed industry with a productive and efficient workforce. Last year, the World Bank said Indians born today are likely to be just 44% productive as workers, way below their Asian peers.

The Annual Status of Education Report shows that half the students (50.3%) in schools lack basic reading ability. The situation with regard to arithmetic is equally abysmal—just 44.1% of class VIII students can do simple divisions.

"Investments in education must be enhanced for meeting the costs of infrastructure, including competent teachers," Ansari said, indicating that efficiency of the system depends on the quality of teachers.