The government has the power to write rules, apply standards, recognise schools, withdraw recognition, and resolve disputes. Our paper teases out the discretionary powers conferred to the state governments for the regulation of education. We study the use of discretionary powers at three touchpoints—the government as a licensor, fee regulator and inspector of private schools.

What did we find?

We find evidence of excesses in the exercise of discretionary powers by the executive—the state education department. Below, we have listed a few instances:

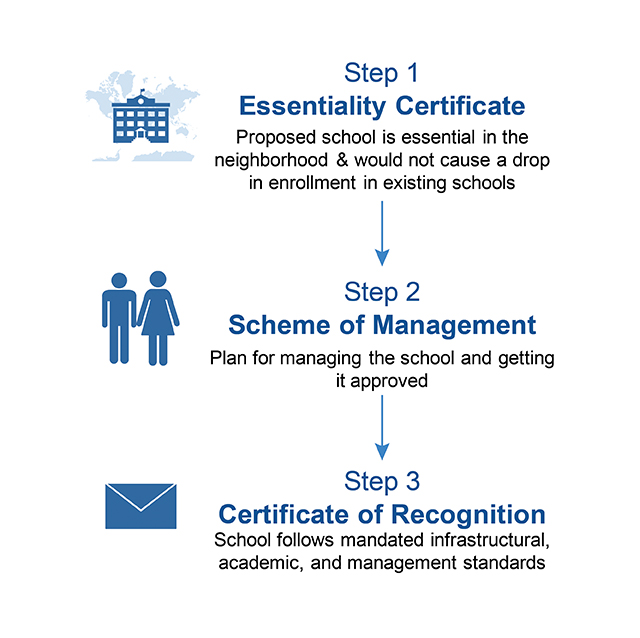

Rigid and intrusive rules that some would argue are ultra vires: There are three key regulatory requirements to open a school in Delhi (Figure 1). Rule 44 of Delhi School Education Rules 1973 authorises the state Administrator to decide if the new school is necessary for the area. This objective has taken the form of an Essentiality Certificate. The Essentiality Certificate, however, does not have a statutory basis in Delhi School Education Act 1973, nor in the Right to Free and Compulsory Education Act 2009.

Proving that a school is essential in an area does not feature in DSEA 1973 or RTE 2009. It only finds a mention in DSER 1973, a glaring instance of quasi-legislative discretionary excess.

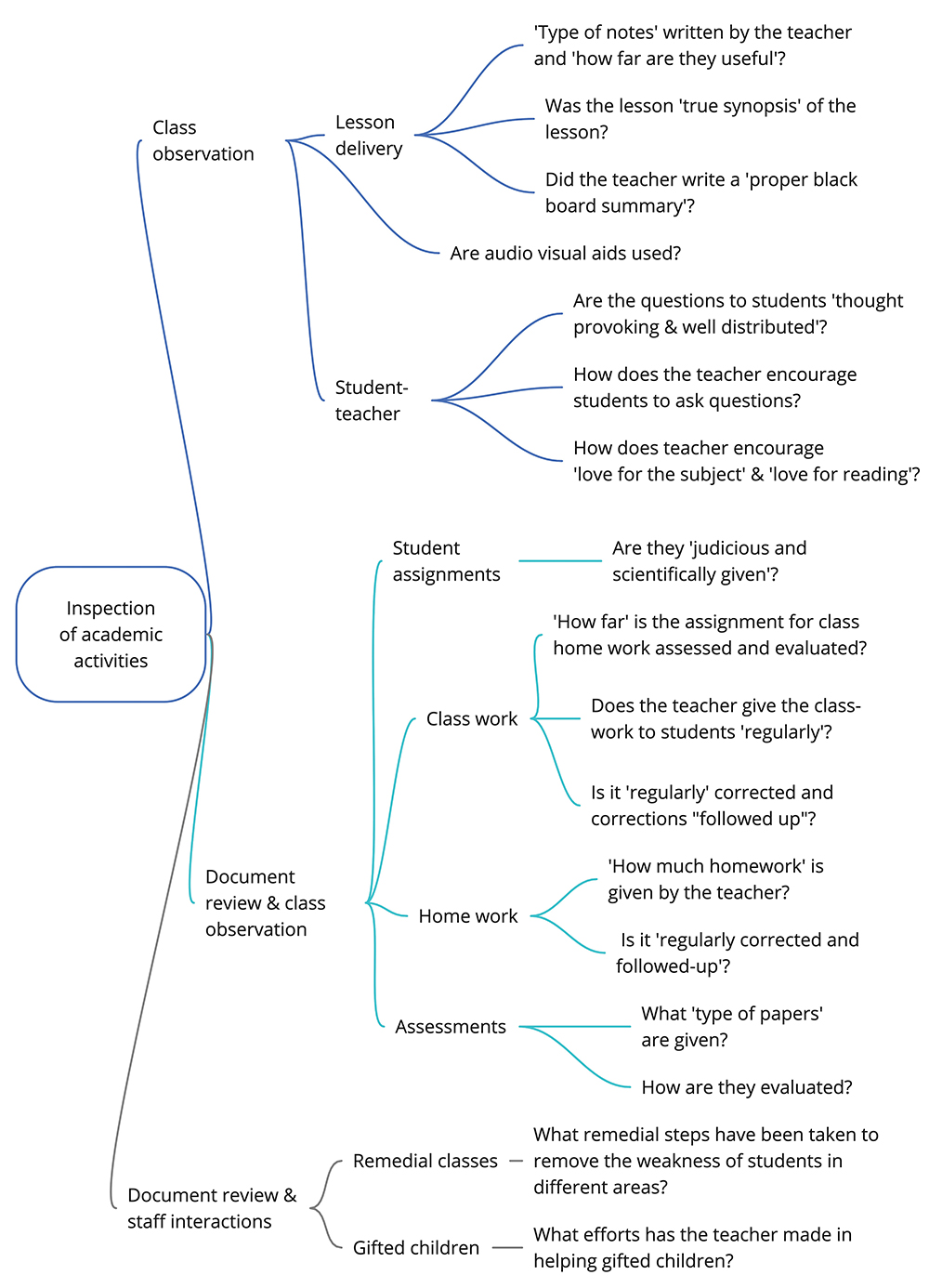

Ad-hoc and arbitrary rule-making: Rule 192 of DSER 1973 states that every inspection should 'be as objective as possible'. A close reading of the proforma that objectivity is a far fetched dream, especially when it comes to academic supervision.

Figure 2 highlights some of the constructs used to evaluate the academic quality of the school.

The first principle of a good questionnaire is to avoid ambiguous/abstract and loaded terms. The question "Were the questions put to the students thought-provoking and well-distributed?" is an example of the former and "Is it (homework) regularly corrected and followed-up?" is an example of the latter.

The absence of objective measures and defined standards for compliance raise many questions: Is evaluation solely dependent on the interpretation of the inspecting officer? If a school gets positive notes on some aspects and negative on others, where does that leave a school? Are reports of different schools comparable?

Poor procedural fidelity and absent transparency on procedures followed: Higher courts in India have in many judgments pronounced an aversion to the commercialisation of education but allowed schools to retain a 'reasonable surplus'. By default, the determination of what would count as a reasonable surplus is left to the administrative machinery.

In 2018, the Directorate of Education in Delhi passed an order instructing all districts to form a Fee Anomaly Committee, as a forum to attend to the complaints of parents. Yet, Fee Anomaly Committees have either not been formed or are defunct.

Parents report that officials often fail to register complaints or take punitive action against schools who do not comply with orders. Given the lack of any codified procedure for processing complaints and limited transparency, it is often difficult for parents to establish a clear complaint trail and follow up.

The Uttar Pradesh Self-Financed Independent Schools (Fee Regulation) Act 2018 regulates fee for schools that charge an annual fee of over Rs 20,000. We found that the fee regulation committees only make decision summaries of its decisions available rather than the full minutes.

Inconsistent and subjective exercise of punitive measures: Section 24(3) of DSEA 1973 authorises the Director to issue instructions to the school manager 'to rectify any defect or deficiency found at the time of inspection or otherwise in the working of the school'. If the 'manager fails to comply with any direction given', then the Director may take any action including— (a) stoppage of aid, (b) withdrawal of recognition, or (c) except in the case of a minority school, taking over of the school'. From this, two challenges emerge.

First, the Director has a free hand in taking any action as deems fit to her if a school fails to comply with any direction. Further, there is no escalation—one mistake and your recognition may be at risk. Second, implementation is skewed—although the Act gives the power to the Director to act as she wishes, measures higher up on the penalty ladder are rarely used.

Learnings for future

Part of these excesses is borne of the lack of documented guidance on how the department should exercise its functions. Others are violations of the letter of the law, sometimes for the understandable reason of limited state capacity. These necessitate the establishment of norms that constrain the actions of those in positions of authority and determining who should be accountable to whom and for what (Posani and Aiyar 2009).

The administrative architecture needs to distinguish and separate the government's role as regulator, service provider, financier, and assessor. Even if full functional separation is a long term endeavour, an independent grievance redressal mechanism is an immediate need to balance executive discretion (Centre for Civil Society 2019).